I’ve been seeing the word ‘taste’ crop up in recent marketing articles and discussions and it triggered a memory that inspires this post.

Rewind a couple of years and I recall hearing something that powerfully affected me as I was wrestling with my own direction in marketing consultancy. It was from someone regular readers will know I often quote, Rick Rubin.

In a 60 Minutes interview Rubin described his work as a producer in the following terms:

“I know what I like and what I don’t like. And I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like. The confidence that I have in my taste, and my ability to express what I feel, has proven helpful for artists.”

When I heard those words, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. And without a second’s hesitation I thought: “Replace the word artists with marketers. That is what I can and should do for a living”. And that’s been my mission ever since.

There’s a strange ambiguity which I am the first to acknowledge. In a great many respects I am a humble and self-deprecating person in matters of IQ. But not on this. Not on EQ and the question of “my taste and the ability to express what I feel”.

I wonder, do you recognise a certainty in yourself about your taste within your area of expertise?

The distinctive power of taste

Whatever your field, whatever your “zone of genius” successful people seem to have the ability to express, rationalise and frame their taste, whilst many others only know how to copy the expressions of others. 5 minutes on LinkedIn, on any given day, will confirm this for you.

Do not confuse taste with popularity. Algorithms wish only to popularise that which conforms with their taste. Oh yes, they have taste, after a fashion. They are designed to reduce human taste to a monoculture.

I recommend Kyle Chayka’s ‘Filterworld: How algorithms flattened culture’ for an in-depth look at that.

I don’t believe you will need me to tell you how those we perceive as taste-makers are attracting a very large audience these days, on any and all sides of politics and culture. One only needs look at who most influenced the last US election to see who is holding sway.

It’s not establishment politicians, or mainstream media, it’s not pop stars or movie stars. It’s people who spend time cultivating distinctive tastes and expressing them in ways other people feel a desire to align with.

That list includes some people who are, at best, pretty disingenuous. Some who are pretty evil. The problem is the combination of taste with outrage. The more outrageous the taste, and the expression, the more attention generated.

But as we tire of outrage, it doesn’t mean we’re tiring of taste.

A new application for taste

I’ve written before about the post-attention economy and what that might look like. I’ve talked about attention and outrage being replaced by prosocial endeavour, about persuasion being an alternative to attention manipulation.

In the age of AI we’re going to be able to create anything. Will we do so tastefully, showing the thoughtfulness of our curation, or with banality? In the last two weeks we’ve seen the Chat-GPT ‘action figure’ craze sweep across social media. Kudos to the first person to think of it. How quickly were you bored by the thousands of people who followed, pumping out their own facsimile?

Crazes aren’t new, but the technology to perform our own instant replication is. The future will certainly include ever-faster, bigger tsunamis of digital monoculture. Taste is how we will signal our distinctive identity.

The creation and dispersal of distinctive taste requires more thought. It’s interesting to me that, as much as short-form content is very popular, longform content is increasingly so as well. YouTubers and podcasters are stretching from 15-30 min episodic content to 90-120 min material with far more depth and finding a hungry audience.

I noticed while writing this piece that Zoe Scaman, an excellent strategist had published a new deck which highlighted taste as one of the three brand superpowers of the future.

Taste gives us an ability to signal our humanity in a world optimised by machines. At the moment everyone is on the efficiency train, but those returns will diminish, they will outstrip human cognitive ability. We will soon tire of feeling gamed.

Taste-based relationships

Having similar tastes is pretty important to human relationships in general.

One of the greatest problems with social media, driven by its desire for growth, has been that it unhooked its relationship to our real-world friends, acquaintances and contacts. Meta has been absolutely clear on this:

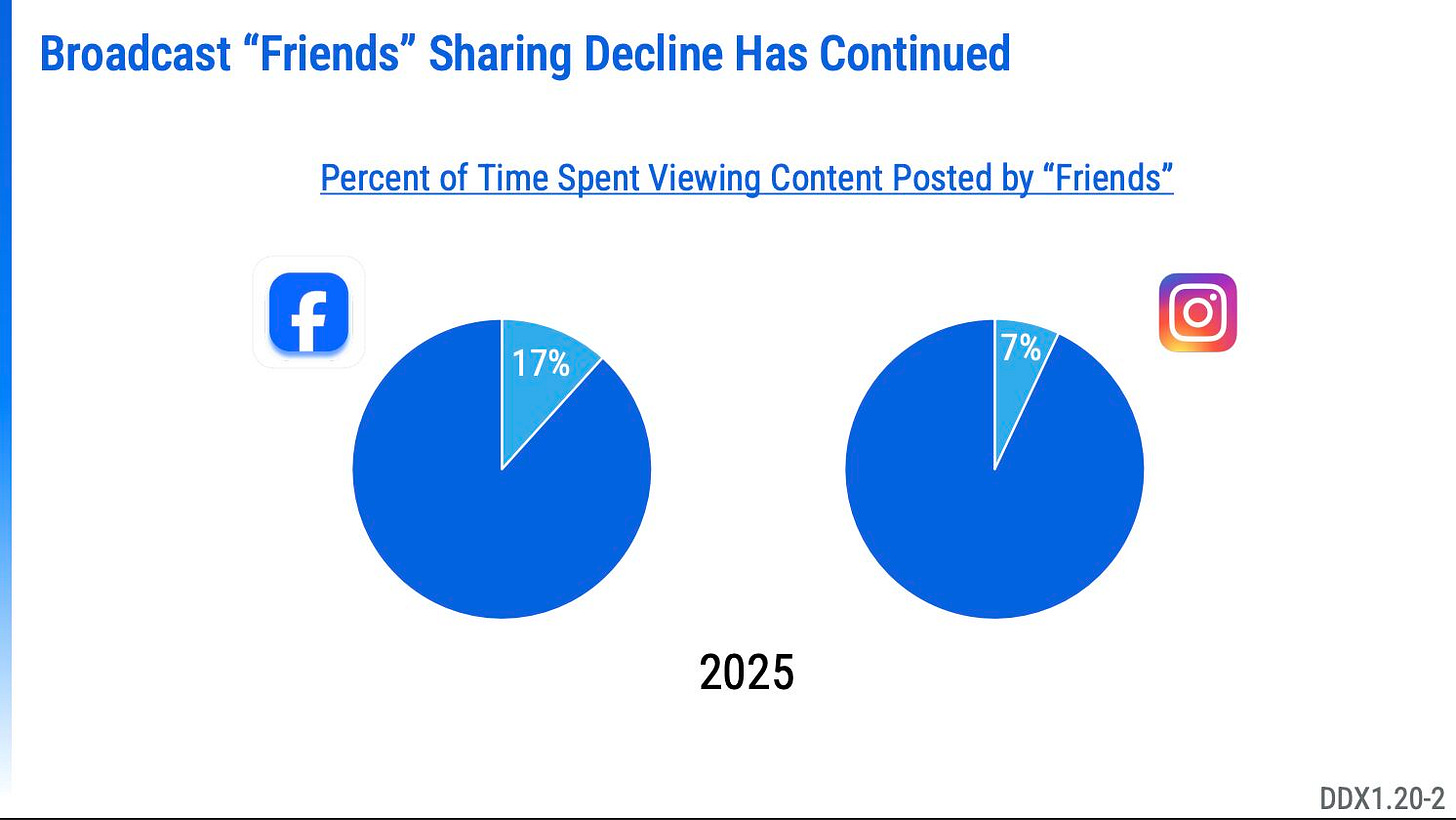

Only 7% of content we view on Instagram has been created by the people we know. LinkedIn much prefers to show us content by those we don’t know, based on the engagement of those we do (a choice I have always found baffling). The interest-graph algorithm is now utterly dominant and is dictating our taste.

In a world where retaining a sense of taste will take intent and effort, some people will be happy to have dopamine served to them in whatever format the algorithms choose. Others will want their control back and, in a consumer context, will want to align with the brands who enable them to have it back. This is a choice for brands. Tastemaker or content dispenser?

If the former, I’m ready to do that work with you.

Reach me via LinkedIn, or the Exodus 25 website.